Оставьте ваши контактные данные и мы обязательно свяжемся с вами

Uzbek family in the XX century.

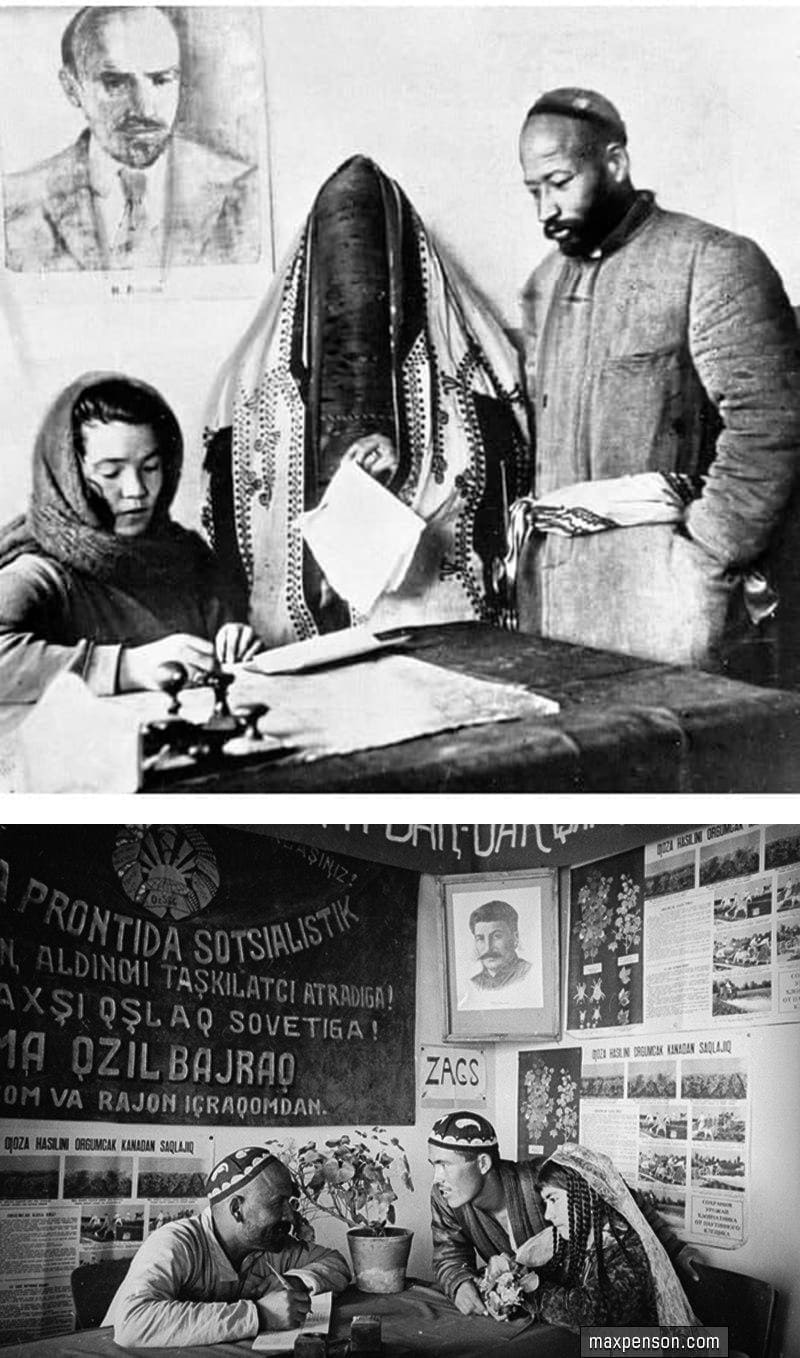

The Uzbek people’s traditional culture and family life underwent significant modifications during the XX century. The majority of significant changes were linked to socio-economic developments and the active introduction of European culture and norms into the lives of the Uzbek people, which played an ambiguous role in this process. Already at the beginning of the XX century, family law rules were altered. Thus, the Soviet state enacted marriage and divorce rules in 1917, and a new marriage and family code was adopted in 1918. Women’s equality was declared in the constitution. For the first time, kalym (bride-price), early marriage, and polygamy were outlawed in 1921. The latter was confirmed in 1926 by the Law of the Central Executive Committee of the Uzbek SSR. These steps taken by the Soviet state played an important role in changing the position of women in the family and society.

But in a more radical way, the equality of women was fuelled by a policy called “Hujum” (Liberation) associated with the removal of the paranji (the veil covering the entire body and face of a woman). The public did not quickly adopt new trends, and the majority of them fought innovations because the emancipation of women from seclusion was partially fulfilled in an atmosphere of violent invasion and destruction of traditional foundations. Many women, on the other hand, were enthusiastic about the changes that fundamentally transformed their lives.

In the 1920s, a major step toward replacing Sharia legal consciousness with new family law was made; all new norms were gradually implemented. Women were granted the right to divorce for the first time. Early marriages were still common in the 1920s and 1930s, and cross-cousin marriages were widely practiced. Throughout the XX century, kalym existed in both hidden and open forms. However, one by one, old premarital and marital norms have become a thing of the past. In the late 1920s, along with religious marriage (nikah), civil marriage was increasingly incorporated into daily life. Marriages have been registered in the registry office since 1927, with the marriage age changing (increasing) and the number of early marriages (at the age of 14–16) decreasing. Backward forms of marriage, such as sororate and levirate, were left in the past. During this time, the number of cross-cousin marriages, which had previously been common among Uzbeks, began to fall. Young people were eventually given the option of selecting a marriage partner. During the postwar period (after WWII), in the 1950s and 1980s, this pattern grew more noticeable. It was due to the development of secondary and higher education that young people had the opportunity to communicate not only at their place of residence – in the mahalla – but also in universities. The criteria for selecting a marital partner have begun to shift, particularly as secondary and higher education have spread. As a result, the potential husband’s degree of education and qualifications were valued, while desirable personal qualities were diligence, kindness, independence, and determination.

Gender segregation and woman’s isolation in choosing a partner have also become things of the past. From the second half of the XX century to the present day, young people have been meeting each other before marriage; it can happen at an educational institution or through relatives and friends. Young people have the opportunity to communicate with each other before deciding on the idea of marriage with their parents. As a result of this expanding practice, pre-wedding communication rituals have emerged. If a young man wants to marry, he makes a proposal and presents gifts. After that, he sends matchmakers if the girl accepts his proposal. However, the tradition of having young people meet each other via matchmaking is widely practiced nowadays. Although the youth today have a free choice, the last word remains with parents, as young people rely on the experience of the elderly in the same way it was at the beginning of the XX century. From the second half of the XX century, the age of marriage has increased. It was related to the need for education, as well as a more serious and responsible approach to starting a family. Girls marry after high school graduation, especially in the village; in the city, after special education, or in the final years of university, whereas men marry later.

In the past, one of the key functions of the family was its economic function. It was preserved during the XX century, notably in rural families, where, despite the generalization of the economy and the development of community farms (kolkhoz), a supplementary personal economy played a major role. This function has almost vanished in urban families.

In the past, one of the key functions of the family was its economic function. It was preserved during the XX century, notably in rural families, where, despite the generalization of the economy and the development of community farms (kolkhoz), a supplementary personal economy played a major role. This function has almost vanished in urban families.

However, the birth, socialization, and raising of children, the administration of family life, and the nurturing of family ties were all significant functions of the family. Intergenerational transmission of ethnocultural customs, which primarily occurred during the socialization of children, has shaped young people’s ethnic identities. Rural families, in particular, sought to have more children (sometimes up to 10 or more) in the first half of the XX century because children were considered future assistants in the economy. The necessity to hold multiple family ritual gatherings, where each family member had his or her own status and duties, as well as the desire to have strong support in old age, all contributed to the desire to have a larger number of children. Socio-economic changes in society triggered the rise of the family’s cultural level and the democratization of family relations, resulting in a shift in preferences for the desired number of children. People began to believe that it was better to have fewer children but financially support them and provide them with a good education. This change in attitude towards the family occurred in the second half of the XX century and became standard practice in the city in the 1970s, while it became the norm in rural areas in the 1980s. Since that period, Uzbek urban families have preferred to have no more than 3-5 children.

Traditionally, the eldest man was considered the head of a family, usually a father or grandfather. Male primacy in the family prevailed throughout the XX century. In 1959, out of 1,682,235 families, 1,403,625 (or 83%) were headed by men, and 278,610 families (or 17%) by women. In 1970, 78% of families in Uzbekistan were headed by men and 22% by women. At the turn of the century, the trend toward women playing a more dominating role in the household accelerated.

With the growing urbanization and increasing ethnic diversity of Uzbekistan’s population, the trend of interethnic marriages began to rise in the second part of the XX century. This trend was especially noticeable in the 1960s and 70s. In 1959, mixed marriages accounted for 8.2% of all weddings, rising to 10.5% in 1979. But at the same time, marriages with representatives of nations of the Central Asian region were preferable.

Введите ваш е-mail адрес, чтобы быть в курсе последних публикаций