Оставьте ваши контактные данные и мы обязательно свяжемся с вами

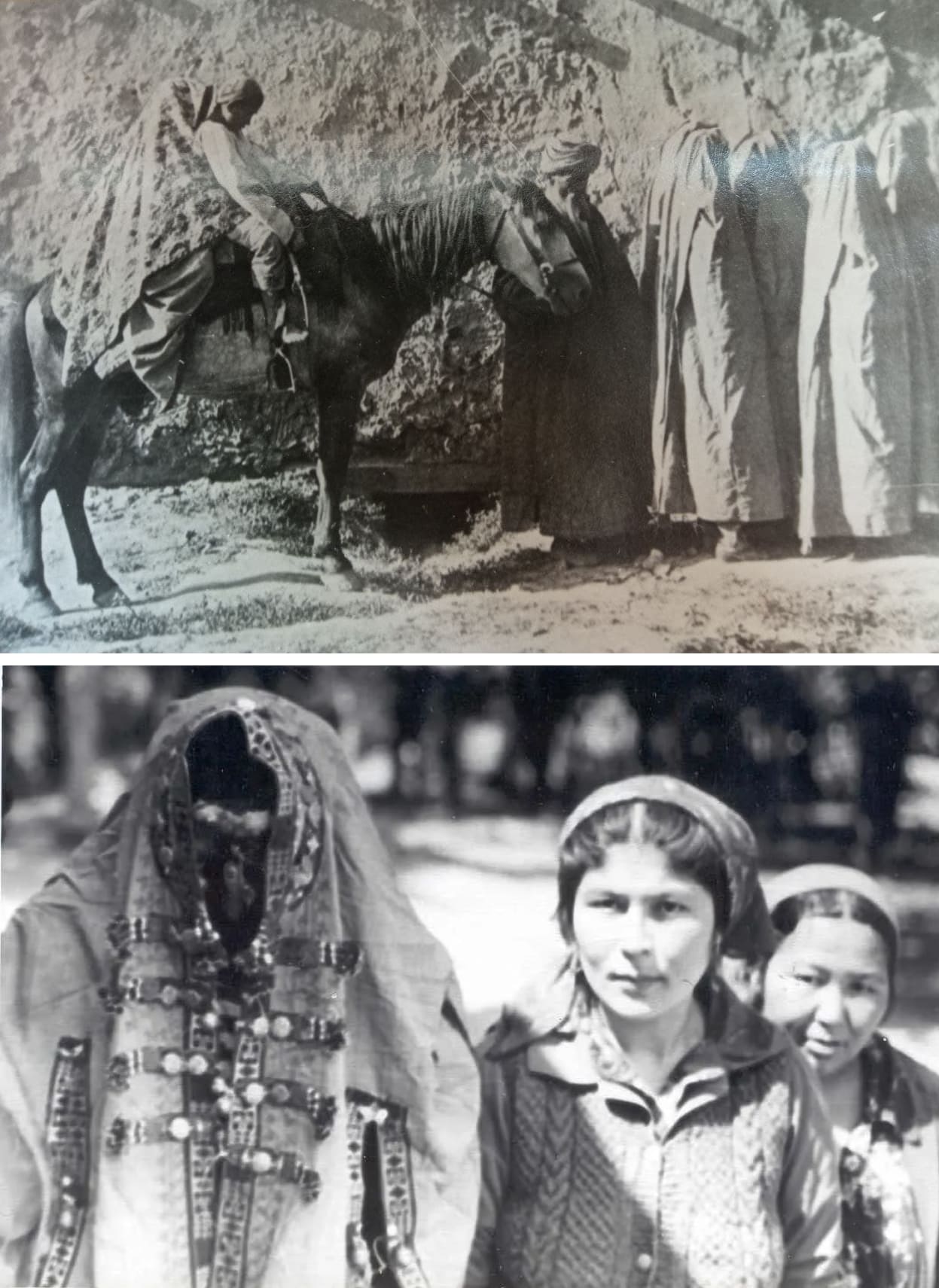

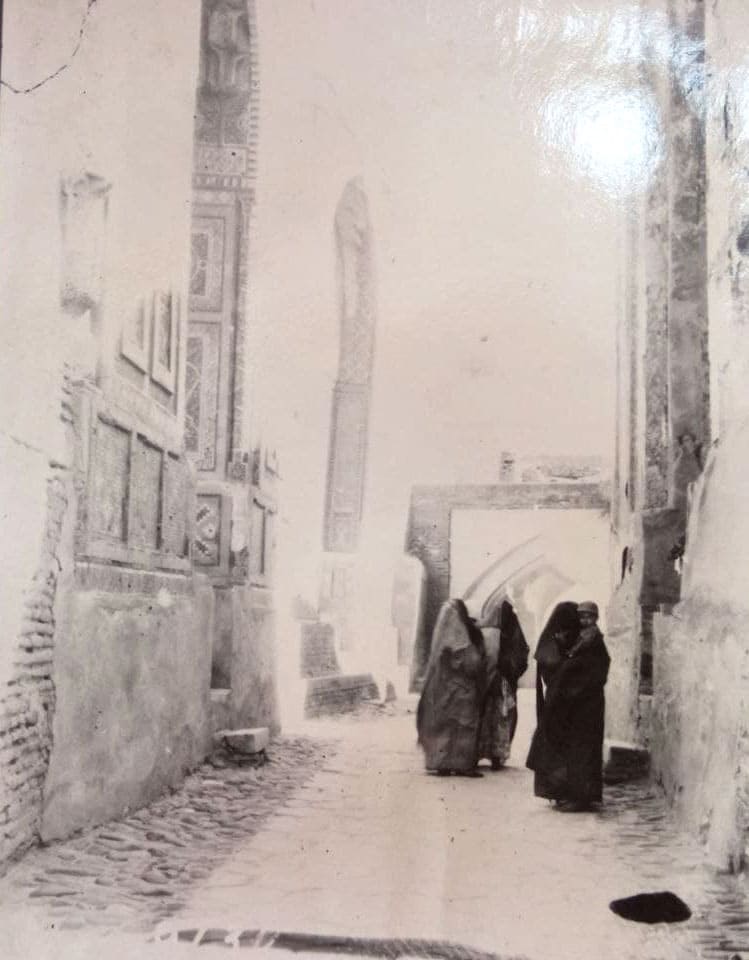

In the second half of the XIX–early XX centuries, there were two main forms of family in the territory of Uzbekistan: a large patriarchal and a small (individual) family. A large family has been characterized by general property, household production, consumption, and a large number of relatives. A large family, also known as a family community, was made up of several generations of close relatives who shared the same yard, grew the same crops, and ate and dressed from the same stocks. The large family consisted of a father, mother, sons, and their children, as well as children of deceased relatives. It could also include the families of the brother (or brothers) of the father, his (or their) wives, and children. In such large families, usually three to four generations were united, and there were 50 people, and in some cases, up to 100 people.

The large patriarchal family periodically changed. Small (individual) families were separated from large families and usually consisted of a husband, wife, and children. At the beginning of the XX century, some families consisted of parents or one of them, and a married son with a child. In ethnographic literature, a family consisting of three generations is commonly called an undivided family. An undivided family existed in many areas in the modern territory of Uzbekistan, and in some areas, such families made up a significant number of families in the village. Undivided families were common among wealthy segments of the population, as well as among representatives of local authorities. They mainly preserved traditional features typical for a big patriarchal family. Also, an undivided family was common among dehkan (peasant) farmers. A large family was called by various terms, but most frequently, katta oila (large family), bir qozon (one cauldron), katta rōzğor (large farm), etc. The head of a large family was usually a great-grandfather, grandfather, father, or any other authoritative member of the family. After the death of her husband, a woman could become the head of the family. A man (or woman) was considered the main manager of the family budget.

All important intra-family issues were decided at the family council (maslahat), where economic issues, holding family celebrations, helping relatives, etc. were discussed. Although the head of the family, married sons, and the eldest wife took part in it, the final decision belonged only to the head of the family. Most families in the late XIX-early XX century were monogamous, but at the same time, polygamous marriages also existed. Polygamy among the peoples of Central Asia was not of a mass nature. It was not only due to religion (sharia), but also to economic opportunities, and therefore, it was mainly common among wealthy families. The economic basis of the large family was land, livestock, residential and farm buildings, and agricultural equipment, which were the common property of the family. The community-family form of ownership was based on the collective work of all able-bodied family members and ensured the preservation of community consumption. Society was negative about separation from a large family. This attitude was reflected in the folk proverb “Bōlinganni bōri er” (The wolf will eat those who are separated). The separation of married sons during the life of their father did not imply a complete distribution of property; as a rule, only “the cauldron was separated”. This meant that parents gave the separated son a dwelling, usually a room, household utensils, and also part of all the stocks in the house, up to firewood. The separation of the son was usually reported to close relatives and neighbors. The basis of the economy—land—remained in the hands of the father, who tried not to allow its division by way of redistribution. Even when one of the married sons died, his widow and children had no right to leave the family. According to custom, she had to marry one of the brothers.

One of the reasons for the collapse of a large family was its growth; if the number of family members exceeded the required standard of land and livestock available on the farm, it could lead to the separation of one or two sons. As a rule, in such cases, the eldest son was separated, so it was enough to restore optimal land norms. There were several other reasons for the separation of a large family – an epidemic, drought, crop failure, a massive loss of livestock, the departure of family members (sons) for earnings, and others, which worsened the family economy and thereby contributed to the collapse of the undivided family community. Separated members of the family lived and managed the household by themselves. However, they maintained close contact with other family members, helped each other, and participated in the performance of various rites and traditions.

With the conquest of Central Asia by the Russian Empire and the penetration of capitalist relations from the second half of the XIX-early XX century, communities began to collapse more often, while relationship customs and norms started to shift and break down. With the development of commodity-money relations, the use of hired labor has started to increase. As a result, more and more sons began to leave their parents’ homes for earnings. The accumulation of personal savings has led to a growing interest in running an independent economy. In such a way, the collapse of a large family occurred.

Forms of Marriage

The marriage of the Uzbeks was endogamous, that is, it was concluded within the clan, so it was unusual for a girl to be married off outside of the clan. This custom most likely was due to economic considerations; the family sought to preserve all family property within a clan. Uzbeks did not firmly adhere to the rules of endogamy. Cross-cousin marriages were popular among Uzbeks, and the most common marriage was between the children of brothers and sisters. Until the beginning of the XX century, levirate and sororate were widespread types of marriage in the everyday lives of Uzbeks. The long preservation of the customs of marrying the wife of a deceased brother (levirate) and the sister of a deceased wife (sororate) is also explained by economic reasons. By marrying the wife of the deceased brother, people tried to preserve the unity of their undivided patriarchal families and the safety of their property.

The most popular form of marriage was kalym (bride-price) marriage. When determining kalym, first of all, the kinship of both parties was taken into account. If the groom and bride were cousins on the paternal or maternal side, then the size of the kalym was relatively small – it barely covered the bride’s parents’ expenses for the wedding evening. The girl’s parents demanded a large amount of kalym if the groom was from a wealthy family or if she was married off outside her village or clan. Kalym was given mainly in money, but in the case of semi-sedentary groups of Uzbeks in the past, cattle were also given as kalym. This is probably related to the ancient traditions of cattle-breeding tribes. After receiving a small kalym, the girl’s parents spent it mainly on a wedding dowry (sep).

Введите ваш е-mail адрес, чтобы быть в курсе последних публикаций